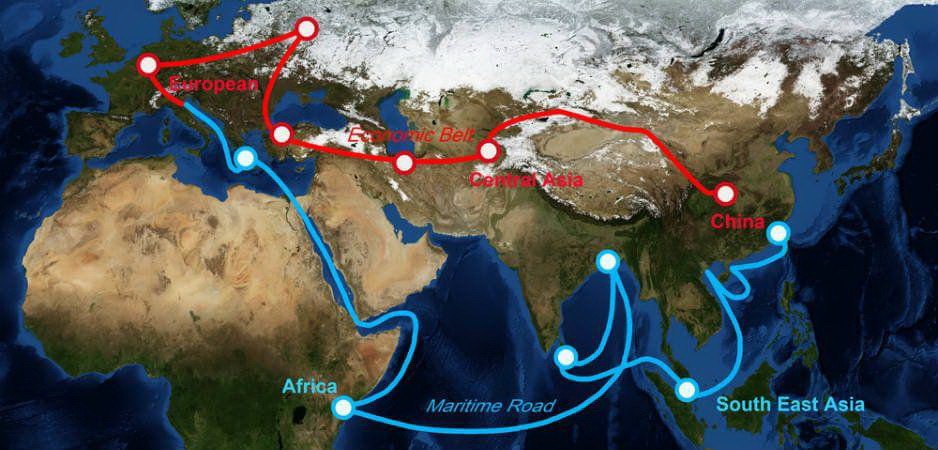

The so-called String of Pearls strategy, a metaphor coined in Western policy circles in the early 2000s, is far more than a shipping map. It’s Beijing’s blueprint for a chain of naval and port infrastructure stretching across the Indian Ocean’s most vital sea lanes. These aren’t just cargo hubs. They’re dual-use platforms—commercial terminals with a built-in military option.

The Naval Dimension

Chinese defense white papers in 2015 and 2019 spell it out: the People’s Liberation Army Navy must “secure energy routes and protect China’s overseas interests.” Translation: permanent Chinese naval access in waters long dominated by the United States, India, and their QUAD partners.

The breakthrough came in 2017, when Beijing opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti. Built to house 2,000 troops and capable of hosting destroyers, amphibious ships, even carriers, the outpost sits at the mouth of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait—through which flows about 10 percent of global seaborne trade and nearly 40 percent of Europe-bound oil. For China, it’s the beachhead that proved the concept.

The Geo-Economics of Sea Routes

Energy dependence drives the strategy. The International Energy Agency estimates China imported 11.3 million barrels of oil per day in 2023, with 72 percent arriving by sea. More than 60 percent of those tankers squeeze through the Malacca Strait, the world’s most notorious chokepoint. That vulnerability fuels Beijing’s determination to scatter “pearls” across the ocean to blunt the risk of a blockade by the U.S. or India.

Among the key nodes:

– Gwadar, Pakistan: Run by China Overseas Port Holding Company,

barely 70 kilometers from the Strait of Hormuz, the artery for

one-fifth of global oil exports. Gwadar is embedded in the

$60-billion China–Pakistan Economic Corridor.

– Hambantota, Sri Lanka: Leased to Beijing for 99 years in 2017,

Hambantota has little cargo traffic but major strategic value. It’s

a pit stop for power projection in the Indian Ocean.

– Chittagong, Bangladesh, and Kyaukpyu, Myanmar: Gateways to the

Bay of Bengal and overland pipelines that bypass the Malacca

bottleneck.

The Logic of “Dual Use”

Beijing insists these are commercial projects. But U.S. think tanks from RAND to CSIS note a recurring pattern: extended piers, dry docks, fuel storage, and security systems that look suspiciously military-grade. In 2022, satellite images spotted a Chinese nuclear sub docking near Hambantota, triggering alarm bells in New Delhi. India sees the pearls as a noose and has doubled down on naval cooperation with the U.S. and Japan under the QUAD framework.

India’s Existential Dilemma

For India, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The country conducts up to 95 percent of its foreign trade by sea, and 70 percent of it flows through waters where Beijing is planting its pearls. New Delhi’s counter is two-pronged: tighten its naval partnerships with Washington, Tokyo, and Canberra, while upgrading its own port network. The Chabahar project in Iran is pitched as the anti-Gwadar—a rival corridor to blunt China’s leverage.

Africa’s Place in the Chain

Africa is no footnote. Beyond Djibouti, Chinese capital is flowing into Kenya’s Lamu, Tanzania’s Bagamoyo, and ports in Mozambique. Between 2010 and 2024, China poured more than $20 billion into Africa’s maritime infrastructure, according to the African Development Bank. Together, these projects stitch into what Chinese planners proudly call the “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.”

The Multidimensional Chessboard of China’s “String of Pearls”

Folded into Beijing’s grand design for a “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road,” the String of Pearls strategy is not just a map of ports. It’s a layered architecture—economic, military, logistical, technological, even cultural—stitched together into a sprawling framework of Chinese global reach.

Port Expansion as the Backbone

Ports remain the core of this play. By 2020, China had a hand in building or upgrading 62 ports worldwide, many scattered across the Indian Ocean but increasingly entrenched in Europe. The crown jewel is Greece’s Piraeus, where Beijing holds 67 percent of the shares. What was once a struggling Mediterranean terminal is now China’s “maritime bridge” into Europe, linking directly into the EU’s TEN-T corridors.

Elsewhere, Chinese operators have bought into terminals at Vado Ligure in Italy, Bilbao in Spain, and strengthened their footprint in the great Northern European hubs of Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Hamburg. The result: not just a logistics chain, but an infrastructure of geo-economic control—an operating system for global trade with China as a root-level user. And thanks to the logic of “dual use,” every port doubles as a potential military node.

Debt, Diplomacy, and Strategic Leverage

The textbook case is Sri Lanka’s Hambantota. The $1.4 billion port project, funded by Chinese loans, ended with Colombo unable to service its debt—and forced to lease the port to a Chinese company for 99 years. Critics labeled it “debt-trap diplomacy,” a phrase that captures how China converts economic leverage into strategic footholds. Similar dynamics are playing out across Africa and Latin America, where Beijing’s infrastructure deals come bundled with political influence over local elites.

Militarization and the Malacca Dilemma

On paper, China admits to just one overseas military base—in Djibouti. In reality, the infrastructure has a shadow military utility. PLA Navy ships routinely use these “commercial” ports for refueling, repairs, and crew rotations. Analysts also point to electronic intelligence capabilities tucked into these facilities, adding to what some call China’s “stealth militarization.”

The playbook isn’t new. The British East India Company in the 17th through 19th centuries built ports and trading posts for commerce but used them as forward operating bases for empire. Beijing is recycling that script with 21st-century tools: globalization, finance, and infrastructure.

The weak link in this strategy remains the Malacca Strait. Barely three kilometers wide at its narrowest, Malacca funnels a quarter of the world’s trade and more than 60 percent of China’s oil and LNG imports, according to the International Energy Agency. A blockade—military, terrorist, or natural—could throttle China’s economy overnight. That’s why Chinese planners call it their “Malacca Dilemma.”

With the U.S. Seventh Fleet and QUAD navies operating in the region under the banner of “freedom of navigation,” Beijing sees a chokehold waiting to be pulled.

China’s Workarounds

To hedge against this Achilles’ heel, Beijing is racing to build

alternatives:

– Overland corridors: pipelines and highways through Pakistan to

Gwadar, and through Myanmar to Kyaukpyu.

– The Iran option: a mooted route via Central Asia to Bandar Abbas

on the Persian Gulf.

– The Kra Isthmus gamble: a proposed canal—or “landbridge”—across

southern Thailand, trimming 1,200 kilometers off shipping routes

and bypassing Malacca altogether.

Each is ambitious, each fraught, but together they reflect China’s refusal to let its maritime lifeline sit at someone else’s mercy.

Sea Power and Strategic Logic

For all the rhetoric of “win-win” development, the String of Pearls is evolving into a naval scaffold. The shift is hardly surprising. As Alfred Thayer Mahan argued in his classic The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1890), maritime dominance has always been the cornerstone of global power. For a 21st-century China more dependent on seaborne trade than any other major state, militarization isn’t a choice. It’s the price of survival.

The case in point: Cambodia’s Ream port. Officially a commercial project, the buildout includes a dry dock and deep-water berths far beyond Cambodia’s naval capacity. The real client is unmistakable—the PLA Navy. Strategically perched at the gateway from the South China Sea to Malacca, Ream is already being described by American think tanks—CSIS, RAND, IISS—as a de facto Chinese naval base.

Conceptual Foundations and Strategic Context

The String of Pearls isn’t a free-floating project. It’s the maritime spine of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, where ships—not trains or planes—carry the real weight. More than 90 percent of China’s trade moves by sea. Rail and road corridors handle just 8 percent, while air freight accounts for a negligible slice under 2 percent. With Russia’s “Northern Route” degraded after 2022 and the “Middle Corridor” through the Caucasus and Central Asia constrained by capacity, the ocean has become the unshakable pillar of China’s global logistics.

At its core, the String of Pearls is an institutionalized maritime architecture of national security—commerce and geo-economics on the surface, naval staging points underneath.

The Post-2022 Logistics Landscape

The war in Ukraine and Russia’s sanctions-induced isolation scrambled Eurasia’s trade geography. In the 2010s, Beijing leaned heavily on overland routes across Russia. After 2022, those arteries shriveled in importance, forcing China to double down on the sea.

The national security implications are stark. By 2024, roughly 72 percent of China’s oil and more than 60 percent of its LNG came in by sea, mostly through the Persian Gulf and Africa. Coal, too—over half imported from Australia and Indonesia—moves along maritime routes. Any disruption to those lifelines would ripple instantly into China’s economy and, by extension, the stability of the Party-state itself.

Port Expansion: Investment, Leverage, Dual Use

By 2025, China had its hand in more than 95 ports worldwide, with over 70 scattered across the Indian Ocean basin. Some stand out:

– Piraeus, Greece: COSCO controls 67 percent of shares,

transforming Athens’ harbor into Beijing’s front door to

Europe.

– Port Sudan: a deep-water port capable of docking Chinese naval

vessels.

– Djibouti: China’s first official overseas naval base, built to

host carriers and nuclear subs, equipped with electronic warfare

systems.

– Gwadar, Pakistan: a keystone of the China–Pakistan Economic

Corridor, giving Beijing a perch over the Strait of Hormuz.

– Hambantota, Sri Lanka: leased for 99 years to China Merchants

Port Holdings after a debt-for-equity swap, securing Beijing’s grip

on India’s southern flank.

– Ream, Cambodia: upgraded to berth Type 055 destroyers,

effectively woven into the PLA Navy’s logistics web.

Each is designed with dual-use baked in—piers, terminals, repair docks, and fuel facilities suited as much to warships as to container ships. The approach matches Beijing’s doctrine of “strategic concealment” (zhànlüè zhéfú), the art of embedding military infrastructure under the cover of economic development.

The Malacca Dilemma

Nowhere is China’s dependence more fragile than the Malacca Strait. This narrow passage—just under three kilometers wide at its tightest pinch—funnels about a quarter of global trade and, by some estimates, as much as 80 percent of China’s imported oil. That makes it not just a choke point but the Achilles’ heel of Beijing’s external strategy.

The U.S. Seventh Fleet patrols the region, alongside QUAD navies, under the banner of “freedom of navigation.” In Beijing’s eyes, it looks like a stranglehold waiting to be pulled.

Diversifying Away from the Strait

China’s risk-hedging playbook unfolds on multiple fronts:

– Overland Arteries: The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

funnels cargo to Gwadar; the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor to

Kyaukpyu. The latter already carries hydrocarbons via pipelines: a

gas line (operational since 2013, capacity 5.2 billion cubic meters

annually) and an oil line (since 2017, capacity roughly 22 million

tons a year). Both ease—but don’t erase—dependence on Malacca.

– Thailand’s Landbridge: The long-dreamed Kra Canal is fading,

replaced by Bangkok’s Landbridge project linking Chumphon (Gulf of

Thailand) and Ranong (Andaman Sea). Backed by massive Thai

investment, the overland “dry canal” looks cheaper, faster, and

politically cleaner. If built, it could siphon off a share of

Malacca’s traffic, saving time and reducing congestion.

– The Arctic Bet: The Northern Sea Route is on the table as a

medium-term supplement to Europe. But thin infrastructure, ice

coverage, and dependence on Russian assets—along with sanctions

risk—make it costly and unreliable. Even as climate change widens

shipping “windows,” it’s an adjunct, not a replacement.

The Portfolio Approach

Beijing isn’t chasing a silver bullet. Instead, it’s constructing a diversified portfolio: Indian Ocean ports as fixed assets, pipelines across Pakistan and Myanmar as bypasses, a Thai Landbridge as a hedge, and Arctic shipping as a supplemental route. Together, they dilute—but don’t eliminate—the possibility of Malacca as a single point of failure.

For China, the logic is clear: in a maritime century, survival depends on redundancy. The String of Pearls is the skeleton. Everything else is muscle.

The Military-Strategic Dimension: From Logistics to Power Projection

The String of Pearls has evolved from a commercial logistics network into a long-range power-projection tool, an almost inevitable trajectory given China’s mounting dependence on sea lanes and the intensifying rivalry with U.S.-led maritime coalitions. The dual-use port network now provides the PLA Navy with several crucial capabilities:

– Sustained presence at long distances. Regular calls by supply ships, destroyers, and submarines at facilities outfitted with extended piers, repair docks, and fuel depots give Beijing operational flexibility stretching from the Bay of Bengal to the Red Sea. Cambodia’s Ream base is a prime example: Chinese-backed upgrades added a dry dock and new pier capable of hosting Type 055 destroyers.

– Intelligence and situational awareness. Civilian terminals and port security systems offer discreet platforms for electronic intelligence collection and surveillance of military and commercial traffic—without the formal designation of “naval base.” Reports suggest China has negotiated selective, exclusive access to critical berths and the potential to deploy air-defense systems, underscoring a creeping “shadow militarization.”

– Control over sea lines of communication. Many pearls are strategically located near chokepoints—the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandeb, and approaches to Malacca. In a crisis, China could leverage its presence to exert pressure, ranging from symbolic shows of force to real constraints on rivals’ access to vital routes.

– Forward basing. Civilian infrastructure can be rapidly militarized for permanent naval deployments. Ream again illustrates the model: what began as a “commercial” upgrade now positions the PLA Navy for sustained operations in Southeast Asia.

Challenges and Counterstrategies

China’s maritime push has triggered a coordinated response:

– QUAD naval activism. The U.S., India, Japan, and Australia conduct frequent joint drills—most notably the Malabar exercises—practicing carrier group coordination, anti-submarine warfare, and joint patrols in the Indian Ocean. This cements a “networked deterrence” architecture.

– AUKUS submarine program. The U.K., U.S., and Australia are expanding nuclear submarine cooperation under SSN-AUKUS, with plans for rotational deployments at SRF-West. This sharpens the undersea challenge to Beijing’s sea lanes by increasing the density of strike and ASW (anti-submarine warfare) assets across the Indo-Pacific.

– Economic and infrastructure competition. The G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) pitches itself as a cleaner alternative to Belt and Road, offering financing with more transparency and political balance—an effort to blunt Beijing’s economic leverage.

– IMEC (India–Middle East–Europe Corridor). This multimodal transport initiative links Indian ports with Gulf states and onward to Southern Europe. Marketed as a “non-Chinese” trade architecture, IMEC aims to undercut Belt and Road’s appeal despite the region’s instability.

– The Cambodian test case. The reopening of the modernized Ream port came with Phnom Penh’s assurances that it would remain “open to friendly navies.” Yet real control of the critical facilities lies with Beijing. For Washington and its partners, that’s a red flag—driving deeper security ties with Cambodia’s neighbors to avoid seeing Ream harden into a full-fledged Chinese naval outpost.

The Counter-Architecture: QUAD, AUKUS, PGII, and IMEC

Taken together, QUAD’s naval exercises, AUKUS’s submarine program, the G7’s PGII financing platform, and the India–Middle East–Europe Corridor amount to a layered web of counterstrategies. Their shared aim is straightforward: restrict Beijing’s room for maneuver and blunt the strategic payoff of its String of Pearls.

The String of Pearls as Systemic Strategy

The String of Pearls is not a scattershot collection of construction projects. It is a systemic instrument of geostrategic engineering for the twenty-first century. It fuses global trade, energy flows, naval logistics, and diplomatic leverage into a single architecture where each “pearl”—whether a port, base, or transport hub—functions as a tile in a larger mosaic.

Its defining feature is hybridity. Officially, these are commercial investments to boost the logistics capacity of partner states. In practice, they are dual-use nodes—facilities that can shift from civilian to military use in a matter of weeks. This erases the traditional line between economics and security, signaling a new form of expansion: the expansion of “latent power,” hidden in plain sight.

An Existential Project for Beijing

The logic is rooted in vulnerability. With over 90 percent of China’s external trade traveling by sea, and up to 80 percent of its energy imports funneled through the exposed Malacca Strait, the String of Pearls has become an existential project of Chinese national security. It reduces the risk of a single point of failure while simultaneously building the foundation for global power projection.

Implications for the Global Balance

The success or failure of this strategy will reverberate far beyond Beijing’s balance sheets. It will shape the resilience of China’s economy and energy system, while redrawing the strategic balance in the Indo-Pacific—a region where the interests of the U.S., India, Japan, Australia, the EU, and much of the Global South converge.

In the decades ahead, the String of Pearls will likely serve as one of the central fault lines of world politics. It embodies a new paradigm in which economic infrastructure, military power, and diplomatic pressure are no longer separate instruments but parts of a fused complex of global leadership.

The competition around this maritime architecture—China weaving its pearls, the West assembling its counter-web—will define the balance of the twenty-first century.

Sources:

- PRC Defense White Paper 2015 — http://www.gov.cn/english/2015-05/26/content_281475122111986.htm

- PRC Defense White Paper 2019 — https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201907/24/WS5d375d9ea310d8305640019d.html

- “Belt and Road Initiative” (official website) — https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn

- Concept of the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” — https://www.beltandroadforum.org

- Chinese naval base in Djibouti (SIPRI) — https://sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2017/chinas-first-foreign-military-base

- Data on Djibouti base capabilities (CSIS) — https://chinapower.csis.org/china-djibouti-military-base

- Satellite images of submarines near Hambantota (Jane’s Defence) — https://www.janes.com

- International Energy Agency (IEA, PRC oil import statistics) — https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-2023

- Analysis of the “Malacca Dilemma” (CSIS) — https://csis.org/analysis/chinas-malacca-dilemma

- Energy Information Administration (EIA, data on the Strait of Hormuz) — https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=41073

- Information on the Bab el-Mandeb Strait (Maritime Executive) — https://www.maritime-executive.com

- Gwadar (CPEC, official page) — http://cpec.gov.pk

- Gwadar — World Bank investment data — https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P101528

- Hambantota (New York Times, “99-year lease”) — https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/world/asia/sri-lanka-china-port.html

- Chittagong (Bangladesh Port Authority) — http://cpa.gov.bd

- Kyaukpyu (Myanmar-China Economic Corridor) — https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/chinas-strategic-port-in-myanmar

- Ream Port (Cambodia, modernization with PRC) — https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/ream-naval-base-09222023150059.html

- Lamu Port (Kenya) — https://lamuport.go.ke

- Bagamoyo Port (Tanzania) — https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/tanzanias-bagamoyo-port-deal-with-china

- COSCO and Piraeus Port (Financial Times) — https://www.ft.com/content/95a2b62c-60b5-11e9-b285-3acd5d43599e

- COSCO in Vado Ligure (Italy) — https://www.portseurope.com/vado-ligure

- COSCO in Hamburg (Deutsche Welle) — https://www.dw.com/en/china-cosco-hamburg-port-stake/a-63560654

- COSCO in Rotterdam (Port of Rotterdam) — https://www.portofrotterdam.com

- RAND Corporation — https://rand.org

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) — https://csis.org

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) — https://www.iiss.org

- IDSA (Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, India) — https://idsa.in

- Chatham House (Indo-Pacific research) — https://chathamhouse.org

- Alfred Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (full text) — https://archive.org/details/influenceofseapo00maha

- British East India Company (historical context) — https://www.britannica.com/topic/East-India-Company

- MALABAR Exercises (official Indian Navy website) — https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/content/exercise-malabar

- AUKUS (official website of the Government of Australia) — https://www.defence.gov.au/about/our-work/aukus

- Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII, G7) — https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/26/fact-sheet-president-biden-and-g7-leaders-launch-the-partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment

- IMEC (India-Middle East-Europe Corridor, G20 New Delhi 2023) — https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/09/09/partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor