In today’s information battlefield, Azerbaijan has become the target of narratives dressed up as “academic debates” but functioning as weapons of propaganda and ideological warfare. These claims don’t just distort history — they aim to chip away at the legitimacy of Azerbaijani statehood, cast doubt on its historical depth and sovereignty, and erode confidence in the very foundations of national identity.

At the heart of this campaign lie three recurring myths, endlessly recycled by outside critics and internal detractors alike: that Azerbaijan is a “young” nation, that it lacks a history of statehood, and that its borders are “artificial.” Peddled as if they were self-evident truths, these talking points collapse under the weight of facts and serious scholarship.

Deconstructing the Myth: What Does “Nation” Really Mean?

Modern nations are not primordial tribes frozen in time. They are products of the modern age — mass literacy, political mobilization, and shared institutions. The architects of nationhood were not “blood and soil” mystics but legislators, schoolteachers, editors, and printers. Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities,” Ernest Gellner’s vision of nations born from industrialization and standardized culture, Miroslav Hroch’s three-phase model of national awakening — all point to the same truth.

Apply this lens to any European society of the 19th or early 20th century, and the outlines are identical to Azerbaijan’s trajectory: from philological and local-history circles, newspapers, and textbooks to political parties, parliaments, and national governments.

Imperial taxonomies, by contrast, were blunt and misleading. The Russian Empire’s label “Caucasian Tatars” for Turkic-speaking Muslims of the South Caucasus was as imprecise as the Ottoman-era habit of calling all subjects “Turks.” Ethnonyms shift with borders, school curricula, bureaucratic languages, and the self-identification of elites. On the ground — from Shirvan and Mughan to Ganja and Karabakh — what endured were not the empire’s filing categories but language, faith, legal traditions, and everyday social networks. Those building blocks formed the cultural bedrock we now call the Azerbaijani nation.

Azerbaijan’s Ethnogenesis in Global Context

The Azerbaijani people emerged from a centuries-long fusion typical of Eurasia: a local Caucasian-Albanian substrate layered with waves of Turkic migration (chiefly Oghuz), the Islamization of the early Middle Ages, a strong Persian cultural overlay, and the cosmopolitan urban mix of Caspian trade hubs. Structurally, this mirrors other nation-building stories: the Turkish nation in Anatolia (a synthesis of indigenous cultures with an Oghuz core), the French (a blend of Gallo-Roman and Frankish elements), or the Russians (an East Slavic foundation enriched by Finno-Ugric and Turkic inputs).

The driving force was the “vernacularization” of elite culture — the trickle-down of high culture into popular use. From the poetry of Khatai (Shah Ismail I) and bilingual court correspondence to mass printing, modern schools, and the pioneering newspaper Ekinchi (1875), Azerbaijani language and identity were standardized, politicized, and broadcast to a wider public. This was not improvisation. It was the same process that defined nationhood across Europe — only denied to Azerbaijan by those intent on weaponizing myths.

Why Azerbaijan’s Political Nation Is a Natural, Not “Artificial,” Phenomenon

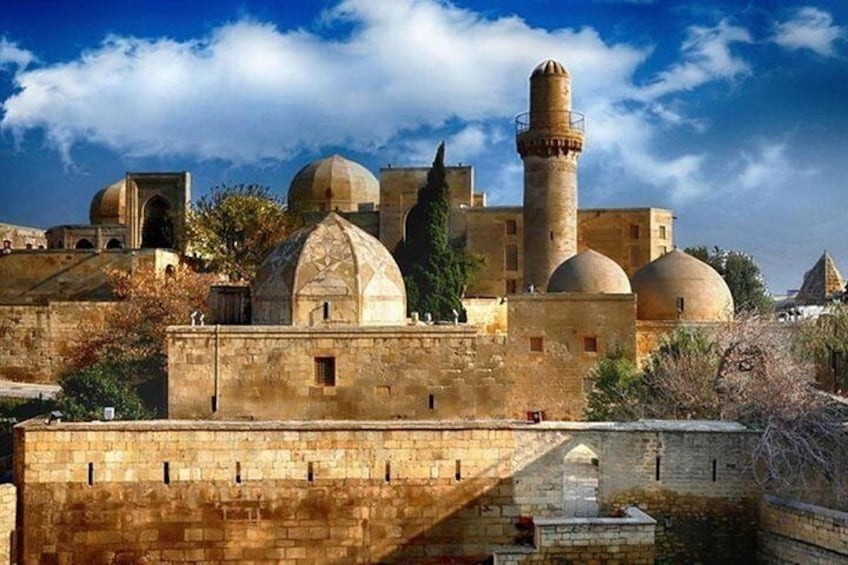

Institutional Continuity of Statehood. The political identity of the territory that is now Azerbaijan has long taken shape in the form of independent or semi-autonomous states. From the Shirvanshahs (9th–16th centuries) to the Atabegs of Eldiguzid rule in the 12th–13th centuries, and later the post-Safavid khanates of the 18th century — Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Shirvan, Quba, Karabakh, among others — these polities carried all the markers of sovereignty: dynastic legitimacy, taxation systems, military mobilization, judicial practices (sharia and adat), and foreign treaties. The Kurakchay Treaty of 1805 between Ibrahim Khalil Khan and the Russian Empire stands as a striking case of international recognition of khanate authority. Even after annexation into the empire (Gulistan, 1813; Turkmenchay, 1828), many institutions survived in the form of autonomies and governorate structures, cultivating habits of local self-governance and training a bureaucratic class that would later serve the republican state.

Modernization and the Socio-Economic Bedrock of Nationhood. Baku’s oil boom at the turn of the 20th century transformed the city into one of the world’s industrial hubs and a laboratory of modernity: trade unions, political parties, a mass press, secular schools, engineering corps, capital accumulation, a bourgeoisie and a working class — the entire infrastructure without which national mobilization is impossible. Baku’s gravitational pull standardized language and politics alike, channeling energy from cultural societies to the rise of “Musavat.” As comparative cases from Prague, Zagreb, and Barcelona in the same era demonstrate, rapid urbanization and multiethnic elite competition generally strengthen, not weaken, the emergence of national consciousness.

The Apex of Hroch’s Phase C: The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918–1920). In just 23 months, the ADR accomplished what marks the birth of a political nation: a parliament that included both parties and minorities, a functioning government, an army, currency, diplomatic missions, de facto recognition from the Entente powers, national flag and emblem, and the founding of Baku University in 1919. Most strikingly, it established universal suffrage with women’s participation — earlier than France and Italy, and decades before Switzerland. This was no fleeting episode but an institutional template to which the independent republic returned in 1991, in full continuity with ADR’s legal framework.

Border Treaties and International Legitimacy. The Moscow Treaty (March 1921) and the Treaty of Kars (October 1921) cemented Nakhchivan’s status under Azerbaijani jurisdiction — a fundamental pillar of international legal continuity. These agreements were not “gifts of history” but products of multilateral negotiations, part of the broader redrawing of borders across Eurasia after World War I — from Fennoscandia to the Middle East.

Europe and the Caucasus: Parallel Trajectories. The argument that “there was no Azerbaijani nation” mirrors claims that “there were no Germans before 1871” or “no Italians before the Risorgimento.” In the era of the Holy Roman Empire, German political loyalty was to local princes and free cities, while cultural identity was multilingual — Latin, German dialects, French at court. In Italy, Massimo d’Azeglio famously quipped, “We have made Italy, now we must make Italians.” Azerbaijan followed the same path: by the time of political consolidation, the essential ingredients were already in place — a common language, a shared space of communication, a collective memory stretching from Shirvan to Karabakh, and thriving economic hubs. The nation-state formula of the 19th–20th centuries was not an “invention out of thin air,” but a codification of what had taken root organically.

Shattering the Myths

– The myth of “artificial statehood” collapses under evidence:

coinage, diplomacy, and treaties from pre-industrial polities; the

modernizing institutions of late 19th–early 20th century Baku; and

the legal continuity that restored independence in 1991.

– The myth of a “young nation” ignores a universal truth of

European modernity: political nations are the inevitable product of

industrialization, bureaucracy, and mass education. Azerbaijan was

part of this continental wave, not an outlier.

– The “Caucasian Tatar” exonym falls apart once we distinguish

imperial filing categories from the self-naming and social

structures of the people themselves. When newspapers, schools, and

parliaments speak in the name of “Azerbaijanis,” the old imperial

labels become meaningless.

Language Reform as Modernization, Not Fragmentation. The shift from Arabic script to Latin in 1929, to Cyrillic in 1939, and back to Latin after 1991 was not a symptom of disarray but part of a broader modern search for effective linguistic platforms in printing, education, and communication. In substance, a unified literary standard and mass press — from Ekinchi onward — did for Azerbaijan what the Czech National Revival, Finnish Lutheran schools, and the French Third Republic did elsewhere: they stitched together cultural space and created a shared cognitive map of the nation.

The Geopolitical Logic of Continuity

In the 20th century, Azerbaijan showcased something rare in the post-imperial world: the endurance of “long lines” that connect the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) of 1918–1920 with the restored independence of 1991. The pattern is unmistakable. Parliamentary institutions were reconstituted, foreign policy reoriented along the same axes — Caspian to Black Sea, Central Asia to Anatolia — and energy infrastructure became the material backbone of national sovereignty. Pipelines and transit corridors were not just about economics; they were sovereign geography, just as railways once “stitched together” Germany and Italy in the 19th century.

Seen through the lens of modern historiography, Azerbaijan does not look like a “young improvisation” but a textbook national history of modernity — complete with an ethno-cultural core, institutional continuity, a modernizing social base, peak moments of political agency (ADR, 1991), and a treaty-based international architecture of borders. Azerbaijan’s trajectory confirms the rule, not the exception, of how nations form. It followed the same logic, the same mechanisms, the same steps as the Germans, Italians, Finns, or Czechs — only played out on the Caspian shore, with its unique blend of Shirvan, Karabakh, Baku, and Nakhchivan. Within this comparative frame, the notion of Azerbaijan’s “inconsistency” as a nation collapses: dismantled by facts, institutions, and an entire epoch of modern nation-building.

Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages: From Atropatene to the “Lands of the Araxes”. Classical Atropatene (Atropatakan) was mapped by ancient authors largely to the south of the Araxes. But late antique and early medieval realities weren’t static provinces on parchment maps; they were interlinked zones of population flows, military formations, craft hubs, and trading markets. To the north lay Caucasian Albania (Arran), bound to Atropatene through overland routes (Tabriz–Ardabil–Barda–Ganja–Shamkir) and a shared agro-pastoral economy on the Mil-Mugan plain. In the late Sasanian period, the marzbans of Arran and Adarbadagan were part of a single defensive system against nomadic incursions. This was one military-economic ecosystem. Chroniclers might have drawn lines; lived reality ignored them.

The Early Islamic Period: Azerbaijan and Arran as a Dual Space. Arab-Persian geographers distinguished between “Adarbayjan” (Azerbaijan) and Arran, but nearly always described them as paired zones — a trade-administrative nexus linking Tabriz–Ardabil in the south with Barda–Ganja in the north. The dynasties of the Sajids (late 9th–early 10th c.), Rawadids, and Shaddadids ruled domains spanning both sides of the Araxes. This matters: fiscal systems, military mobilization, and caravan logistics functioned as one mechanism. In contemporary usage, the term “Atropatenian” or “Azerbaijani” didn’t stop at the southern banks of the Araxes; it denoted a political core that pulled in the surrounding lands of Arran and Shirvan.

The Atabegs and the “Northern Vector” of Azerbaijan. The Eldiguzid Atabegs of Azerbaijan (12th–13th c.) shifted the political center of gravity northward: Nakhchivan, Ganja, then Baylaqan (Shamkir) and Tabriz formed the spine of their realm. Their title was explicit — “Atabegs of Azerbaijan” — and their domain stretched from Tabriz into Arran and Shirvan. This was no semantic flourish but administrative reality: tax collection, garrisoning, land grants, and governor appointments ran in a single circuit. From a historical-geographic perspective, this was the macro-region of “Azerbaijan” — a politico-economic core with northern “shoulders” essential for communication and cohesion.

The Safavid Synthesis: The Qizilbash as the Cement of Space. In the 16th–17th centuries, the Qizilbash military elite — linguistically, culturally, and politically Azerbaijani — forged a coherent arc stretching from Ardabil and Tabriz to Karabakh, Shirvan, Shaki, and Baku. Tabriz was the first capital, Ardabil the spiritual hub, Karabakh the strategic bastion, Shirvan the tax and craft reservoir, and Baku the export port for wool, hides, fish, and eventually oil. Provincial beylerbeyliks, including Karabakh, were tied directly to the Safavid capital, while Azerbaijani Turkic served as the lingua franca of court and administration. This was the historical-political matrix of a unified Azerbaijan.

The 18th Century: Khanates as Fractured but Connected Polities. After the death of Nadir Shah in 1747, a mosaic of khanates emerged: Karabakh (capital Shusha), Ganja, Shaki, Shirvan, Quba, Baku, Derbent, Talysh in the north; Tabriz, Urmia, Khoy, Ardabil, Maragha in the south. Yet elite intermarriages, trade fairs, and artisan migrations kept budgets and trade routes flowing across the Araxes. Merchants from Shusha traded in Tabriz, while Talysh and Javanrud networks supplied Baku and Lankaran. Rivalries existed, but geography compelled cooperation: the pastoral economy of Mil-Mugan, Karabakh’s vineyards, Shaki’s silk industry, and Tabriz’s trade fairs were complementary subsystems of a single economic model.

In other words, from antiquity to the 18th century, Azerbaijan’s political, economic, and cultural life was a shared ecosystem across both banks of the Araxes — a continuum that explains why the modern Azerbaijani nation is neither an improvisation nor an accident, but the natural outcome of deep-rooted historical processes.

The Russo-Persian Wars and the Araxes Divide: Political, Not Ethnic

The wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828, along with the Treaties of Gulistan (October 24, 1813) and Turkmenchay (February 21, 1828), carved out a division across the Araxes River that was military-political rather than historical-ethnic. Folded into the Russian Empire were the khanates of Northern Azerbaijan — Karabakh, Ganja, Shaki, Shirvan, Quba, Baku, Derbent, and Talysh; and, after Turkmenchay, Nakhchivan and İrəvan. The new border along the Araxes split the macro-region into “north” and “south,” with immediate consequences: trade routes were reoriented, land and waqf jurisdictions shifted, tax flows redistributed, and organized population transfers initiated. Between 1828 and 1830, tens of thousands of people resettled from Persian and Ottoman lands into the newly designated “Armenian” region of the empire and nearby districts. This reshaped the confessional and ethnic makeup of certain northern counties but did not sever the cultural-linguistic continuum of the Azerbaijani world, which continued to reproduce itself through family ties, markets, and language.

The clear historiographic conclusion is this: the modern Republic of Azerbaijan is the successor state to the northern half of historic Azerbaijan, which underwent autonomous modernization under the Russian Empire and the USSR — industrial urbanization in Baku, railroads, oil exports, schools, and a national press. Southern Azerbaijan, by contrast, evolved within Iran’s jurisdiction. This divergence of political-legal trajectories within one cultural-historical space parallels the Polish partitions under Prussia and Austria, or the Irish case — Ireland and Northern Ireland: one civilizational fabric, cut by imperial force.

Name and Identity: Why “Azerbaijan” Is Not “Only Iran”

The claim that “Azerbaijan” belongs exclusively to Iran is an anachronism. First, the very name “Azerbaijan/Adarbayjan” in medieval usage referred to a core around Tabriz and Ardabil, but the political “shadow” of that core consistently extended over Arran, Shirvan, Karabakh, and Nakhchivan. Second, the linguistic and ethno-cultural consolidation of Azerbaijani Turks was a two-sided process: the Oghuz-Turkic core that took shape under the Seljuks and the Qizilbash was forged across the “south–north” arc, which never matched today’s interstate border. Third, when the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was proclaimed in 1918, the choice of name didn’t “create” a link; it articulated an existing reality. Southern Azerbaijan remained under Iranian rule, but the language, folklore, mugham music, cuisine, artisanal standards, and marriage networks bound together communities from Urmia and Tabriz to Shusha, Ganja, and Baku.

Look not at slogans, but at statistics and infrastructure, and the unity becomes obvious:

– Trade corridors. The caravan route

Tabriz–Ardabil–Barda/Ganja–Shamkir in medieval times, and later the

rail and highway links anchored in Baku’s port, gave the south

access to the Caspian and the north access to Iran’s markets and

raw materials. The Araxes was a bridge, not a moat.

– Pastoral-agricultural synergy. Seasonal herd migrations between

the Karabakh plateau, the Mil-Mugan plain, and southern winter

pastures formed a “two-season economy” that only functioned with a

permeable Araxes. This was not incidental custom but the structural

economic geography of the region.

– Urban networks. Tabriz and Shusha exchanged craftsmen and goods;

Baku drew in merchants from across the arc; Ganja and Nakhchivan

functioned as transit hubs. The migration patterns of the 19th

century, intensified by Baku’s oil boom, only reinforced this

web.

– Linguistic-cultural continuity. The dialectal continuum of the

Azerbaijani language — with northern and southern zones — is a

textbook case of sociolinguistic coherence: phonetics, vocabulary,

folklore formulas, wedding and funeral rituals, musical modes —

variable, but uninterrupted.

Comparative Framework: How Macro-Regions Work

– Alsace-Lorraine. A region that shifted between France and

Germany multiple times while maintaining a durable cultural code.

No serious historian calls Alsace “only French” or “only

German.”

– Punjab. The 1947 partition produced two states and two

jurisdictions but left intact a common agricultural and trading

history, language, and cultural markers. The divide was political,

not ontological.

– Ireland/Northern Ireland. Different state frameworks, one

historical island space with intertwined economies, cultures, and

identities.

Northern and Southern Azerbaijan must be understood the same way: not as separate “histories,” but as two political-legal trajectories within a single historical-cultural space.

Dynastic and administrative practice (Sajids, Eldiguzids, Safavids) shows governance across both banks of the Araxes with the Azerbaijani core as reference. Economic geography (Mil-Mugan, Baku’s port, Tabriz fairs) reveals structural interdependence of northern and southern zones. Linguistic-cultural continuity undermines any notion of “different worlds”: this is one people, with dialectal variation but a shared matrix. The 19th-century division under Gulistan and Turkmenchay was a product of Russo-Persian power politics, not a “natural” boundary of ethnicity or culture.

To deny the historical connection of Azerbaijan’s northern lands to the name “Azerbaijan” is as absurd as denying Île-de-France its link to northern France because a southern France exists, or stripping Alsace of identity because it changed hands between empires. That’s not how the history of macro-regions works. What it preserves is not rigid divides but resilient systems of interdependence. Azerbaijan belongs in that category: a historic unity split by 19th-century treaties, yet still carrying its cultural and socio-economic core. The modern Republic of Azerbaijan rightfully stands as the heir of the northern half of this whole — with its own modern trajectory, yet anchored in the memory of a space conceived and developed as one.

Statehood as a Historical Continuum: Khanates as a Form of National Organization

The claim that Azerbaijan “never existed as a unified state” and was nothing more than a patchwork of khanates is not just a distortion of history — it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of how statehood develops. Every nation’s history is marked by cycles of centralization and fragmentation. It is precisely within that dynamic that national identity takes root.

Across the lands of modern Azerbaijan and northern Iran, powerful political formations arose over the centuries that are undeniably part of Azerbaijan’s statehood heritage. The Shirvanshahs ruled for nearly 800 years (8th–16th centuries). The Atabegs and the Hulaguids (12th–14th centuries), the formidable tribal confederations of the Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu (14th–15th centuries), and finally the Safavid Empire (16th–18th centuries), founded by an Azerbaijani dynasty whose court and army spoke Azerbaijani Turkic — all stand as milestones. In European historiography, such dynastic continuity is treated as solid proof of deeply rooted statehood. When it comes to Azerbaijan, however, detractors seek to deny it.

The period of khanates (late 18th–early 19th centuries) was the natural outcome of the collapse of Safavid and Afsharid central authority. This was hardly unique to Azerbaijan. Germany, after the decline of the Holy Roman Empire, remained fragmented until unification in 1871. Italy, prior to 1861, consisted of dozens of duchies, kingdoms, and republics. Russia, too, experienced a long era of principalities following the fall of Kievan Rus. No historian equates these periods of fragmentation with an “absence of statehood.” In fact, German and Italian historiography often sees these centuries as stages of cultural consolidation that laid the foundation for later unification. Why, then, should Azerbaijan be judged by a different standard?

The khanates of Karabakh, Shaki, Shirvan, Baku, and Ganja possessed all the attributes of statehood in their time: armies, treasuries, tax systems, and diplomacy. They signed treaties with Russia, Persia, and the Ottoman Empire, functioning as subjects of 18th-century international law. A shared language, a common Islamic faith, legal traditions rooted in sharia and adat, and parallel administrative structures all tied the khanates into one civilizational space, not a scatter of “accidental fragments.”

Critics often claim, “There was no united Azerbaijan, only fragmented khanates.” But by that measure, Germany, Italy, and even Russia “did not exist” as recognizable states before the 19th century. The division of Azerbaijan’s historical-cultural space in the 19th century cannot be cast as some “natural” evolution or proof that Azerbaijanis lacked statehood. It was the direct result of imperial geopolitics — the collision between Russia and Persia — and the treaties that sealed their balance of power: Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). Those agreements drew a new border along the Araxes, artificially splitting the Azerbaijani people into north and south. The entire modern debate over Azerbaijan’s “legitimacy” stems from ignoring this imperial partition.

Historical Parallels of a Divided Nation

This is hardly unique to Azerbaijan. Korea, for over 1,500 years, existed as a unified civilization with a shared language, culture, and statehood — from Koryo to the Choson dynasty. But after World War II, outside powers — the USSR and the U.S. — sliced it at the 38th parallel. That division remains one of Asia’s most explosive geopolitical flashpoints. Germany, too, was carved apart in 1949 into the FRG and the GDR, despite a millennium of statehood stretching from Charlemagne to the Kaiserreich. The Kurds are an even more tragic case: a people of over 30 million, divided by the colonial Sykes–Picot borders into Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria — their national question unresolved to this day.

Placed in this context, the Republic of Azerbaijan is the natural historical heir to the northern half of a once-unified Azerbaijan that fell under Russian rule after the imperial partition. To call Azerbaijan an “artificial” creation is to ignore the very logic of world history, where the borders of nations and states have so often been shaped by wars, treaties, and foreign intervention. Far from an anomaly, Azerbaijan is a textbook case of how nations endure through cycles of fragmentation, reorganization, and renewal.

The Myth of “Fragmented Khanates” and the European Experience

Critics of Azerbaijan often point to the era of khanates as supposed evidence of the nation’s lack of statehood. But this line of argument reveals a shallow grasp of how political organization worked in the feudal age. Almost every major European nation passed through long periods of fragmentation before unification.

Germany before 1871 was a patchwork of more than 30 entities — kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and free cities. Only Otto von Bismarck’s iron-willed statecraft forged this quilt of sovereignties into a single empire. Yet no one today argues that the German nation “did not exist” prior to 1871.

The same goes for Italy. Until Garibaldi and Count Cavour engineered unification in 1861, the peninsula was split between the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the Papal States, Tuscany, and numerous duchies. Yet modern Italy is proudly claimed as heir to both the Roman Empire and the Renaissance. In feudal Europe, multiple centers of authority never negated the existence of an ethnocultural community.

Modern Middle Eastern and Asian states tell the same story. Saudi Arabia emerged as a unified kingdom only in 1932, when Abdulaziz ibn Saud consolidated Najd, Hejaz, al-Hasa, and other regions. The United Arab Emirates came together in 1971 as a federation of emirates, each with its own dynastic traditions. No one disputes their statehood because of that history.

By the same standard, when the Republic of Azerbaijan was declared in 1918, it was the political embodiment of a statehood forged over centuries. The argument about the “absence of a single center” collapses once you recognize that the very concept of the modern nation-state is a 19th–20th century invention.

The “Iranian Azerbaijan” Argument in Historical-Geographic Context

Claims about the “true Azerbaijan” being confined to the Iranian provinces ignore the most basic truth: state borders are fluid, shifting with wars and treaties. The historic region of Azerbaijan (Atropatene) encompassed both northern and southern lands east of Lake Urmia. It was here, in the 4th century BC, that the satrap Atropat established the polity that gave its name to the entire region.

The actual division of Azerbaijani lands came only after the Russo-Persian wars and the Treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). The northern khanates were incorporated into the Russian Empire, while the southern ones remained under Persia. This was not an ethnic or cultural break but an imperial demarcation line. Thus, the Republic of Azerbaijan is the natural heir to the northern portion of historic Azerbaijan, which entered the Russian orbit and, in 1918, seized the opportunity for independence.

By contrast, the Russian Federation — which often claims an unbroken lineage of “ancient Rus” — rests on a far more fragmented and contested past.

Moscow’s Path: From Vassal to Empire

After the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, all the Rus’ principalities fell under the Golden Horde. Moscow rose precisely because of its loyalty to the khans: princes secured charters of rule (yarlyks), the right to collect tribute, and military authority only as agents of the Horde. This dependency, not independence, gave them leverage over rival princes.

Ivan Kalita’s elevation as Grand Prince was a direct result of his service to Khan Uzbek. The title was not earned through sovereignty but granted in exchange for loyalty.

Through the 14th and 15th centuries, Moscow expanded by absorbing Tver (1485), Yaroslavl (1463), Novgorod (1478), Pskov (1510), and Ryazan (1521). Many of these takeovers were either military conquests or sanctioned interventions by the Horde, which decided who would be its chief vassal in Rus’.

Even after Moscow broke free at the “Great Stand on the Ugra” in 1480, it continued to build its power not as a rebirth of “ancient Rus” but through conquest. Ivan IV seized Kazan in 1552, Astrakhan in 1556, and by 1582 Muscovite expansion had begun in Siberia — all Turkic Muslim polities, heirs of the Golden Horde.

In reality, Moscow’s rise was closer to the making of a colonial empire than the restoration of an ancient state. It was an expansionist power that subdued diverse ethno-political entities rather than a “gatherer of ancestral Russian lands.”

The Lesson for Azerbaijan

If fragmentation and conquest do not delegitimize German, Italian, or Russian statehood, why should Azerbaijan be judged differently? The khanates were not proof of absence, but a stage in the same universal cycle of state formation: fragmentation, consolidation, and reconstitution. The modern Republic of Azerbaijan stands firmly within that continuum — the rightful heir to centuries of state tradition, shaped not in isolation but through the same historical forces that forged every modern nation.

Empire-Building and the Myths of Continuity

For clarity, it helps to draw a parallel with the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans, emerging from Anatolia, gradually subjugated the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa. No serious historian claims the Ottomans were heirs to some single ancient state that once encompassed those regions. Their empire was the product of conquest and diplomacy. In much the same way, Muscovy built its state step by step, subordinating diverse regions through military campaigns and shrewd alliances.

Another instructive case is the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. It draped itself in the mantle of Rome but was in reality a patchwork of territories stitched together by German kings. Moscow adopted a similar fiction with its ideology of the “Third Rome.” This was never a concrete inheritance, but an ideological construct designed to legitimize power.

By the 17th century, the Tsardom of Muscovy spanned more than 5 million square kilometers. Yet less than half of that space could be considered ethnically Russian. Vast swathes were Turkic, Finno-Ugric, Siberian, and Caucasian. In truth, Russia — and its successor, the Russian Federation — grew not out of some “ancient statehood,” but as an empire of conquest.

Russia is not the direct descendant of Kievan Rus’ or a mythical “unified ancient Rus’ state.” Its genesis lies in the political maneuvering of the Muscovite principality, which balanced service to the Golden Horde with the suppression of neighboring rivals. Moscow became dominant not because it was “the oldest and strongest” but because it proved the most loyal vassal to the Horde — and later, the first to exploit its collapse for expansion.

Azerbaijan’s Civilizational Foundations

Here the contrast with Azerbaijan is stark. Azerbaijan can claim state traditions stretching back millennia: Caucasian Albania, Atropatene, the states of Turkic dynasties, and the layered cultural legacy of the Caspian crossroads. Russian statehood was constructed as a colonial empire from the 16th century onward; Azerbaijani statehood, by contrast, rests on a civilizational foundation that matured organically across centuries.

The culmination of that long arc came on May 28, 1918, with the proclamation of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR).

This was an event of monumental significance:

– The ADR became the first secular parliamentary republic in the

Muslim world.

– It granted women the right to vote — earlier than many European

countries and even the United States.

– It created all the attributes of sovereignty: a parliament,

government, army, national bank, and education system.

– It formalized the nation’s political self-identification under

the name Azerbaijanis.

The ADR was not a “first experiment,” but the logical outcome of centuries of national development expressed in the political language of its time. Its brief lifespan — just 23 months — was cut short solely by external aggression from Soviet Russia, not by any internal failure.

The Legacy Today

The modern Republic of Azerbaijan, which restored its independence in 1991, stands as the constitutional and political heir to the ADR. This continuity underscores the essential point: Azerbaijan’s statehood is neither artificial nor improvised. It is the product of deep historical tradition, long cycles of political organization, and the modern affirmation of sovereignty that began in 1918 and was reasserted in 1991.

Far from being a “patchwork” or a colonial construct, Azerbaijan represents one of the most authentic examples of nationhood in the broader Eurasian story — a state with ancient roots, a modern democratic legacy, and a future grounded in the logic of history itself.

Let’s be clear about the record:

The Azerbaijani nation-building process fits squarely within the global historical paradigm. It unfolded by the same logic that shaped Germany, Italy, and countless others. There is nothing “exceptional” or “artificial” about it. The term Azerbaijan has deep historical roots. It is a legitimate name both for the ancient region and for the modern state established on its northern half. The khanate era was a lawful stage of feudal statehood, not evidence of its absence. The parallels with German principalities and Italian duchies are direct and undeniable. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 1918 is an irrefutable milestone — proof of the maturity of national consciousness and the political will of the Azerbaijani people.

Claims that Azerbaijan is “artificial” or “too young” are not grounded in scholarship. They are born of politically motivated speculation, crafted not to uncover truth but to damage Azerbaijan’s international standing and question its sovereignty. Serious historical research — based on facts rather than prejudice — rejects these narratives as baseless and ahistorical.

Assertions about Azerbaijan’s “historical youth” or “fragility” are not analysis; they are tools of hybrid warfare. Their purpose is to delegitimize the state and deny its people the right to self-determination within internationally recognized borders.

History is replete with nations that gained statehood in the modern era through the consolidation of previously fragmented lands: Germany in 1871, Italy in 1861, Bulgaria in 1878, Finland in 1917, Israel in 1948, the Republic of Korea in 1948 — and dozens more. Azerbaijan belongs in that same continuum. This is not an anomaly. It is the normal, global pattern of history.